In northwestern New Mexico sits Chaco Culture National Historic Park; a sweeping collection of ancient ruins attribnuted to the height of Ancenstral Puebloan culture. The Ancestral Puebloans, often referred to as the Anasazi, were a complex Pre-Columbian society that inhabited much of the Four Corners region in modern day Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. On a continuum, this culture group became recognizable from their neighbors approximately 1500 BCE and most of their settlements were abandoned around 1300 CE when they migrated to the Pueblos of today. The Ancestral Puebloans are known for their enigmatic cliff dwellings, elaborate stone architecture, distinctive Kivas, and finely-crafted pottery. However, in Chaco Canyon there exists compelling evidence that these people were not just engineers and architects, but astronomers as well.

Fajada Butte, also known as Banded Butte, is a 135 meter erosional remnant of sedimentary rock that rises above the surrounding plain. Its slopes contain the ruins of small cliff dwellings and

countless fragments of broken pottery. By dating the ceramic artifacts, archeologists estimate these structures were in use between the 10th and 13th centuries. There is also evidence of a 95-meter-high, 230-meter-long ramp on the southwestern face. The scale of this construction and the absence of any utilitarian use suggests this was a location of great ceremonial importance. This notion is bolstered by the presence of an elaborate series of petroglyphs known as “The Sun Dagger”.

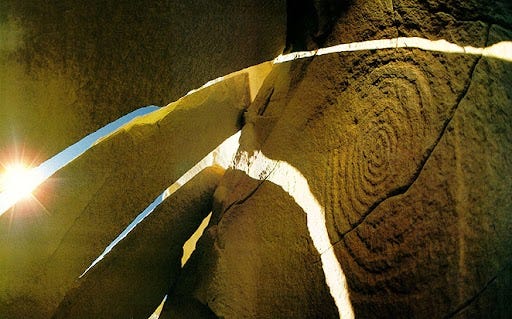

In 1977, artist Anna Sofaer visited Chaco Canyon on a volunteer survey to record rock art. Located on a southeastern facing cliff near the summit of Fajada Butte, she noticed three large slabs of stone leaning against the rock face. Through narrow openings in the hand-placed stones, slivers of sunlight were cast onto a pair of spiral petroglyphs etched into the cliff wall. At about 11:15 AM on the Summer Solstice, a dagger shaped beam of light bisects the larger of the two spirals. On both the Vernal and Autumnal Equinox, the dagger of light reappears, though in a different

position. Finally, on the Winter Solstice, a pair of daggers shine on each side of the same spiral. Likewise, the spirals appear to track the Lunar minimum and maximum through the appearance of shadows at each extreme of the nine-and-a-half year cycle.

While scientists and archeologists still debate over whether the shadows tracking Lunar movement were purposeful or not, there is clear consensus that the daggers of light were intended to mark each Solstice and Equinox. Regardless, the technical and mathematical skill to create The Sun Dagger shows that the Ancestral Puebloans of Chaco Canyon, and likely beyond, were skilled observers of the stars and celestial bodies. Unfortunately, due to the settling of one of the slabs, the dagger no longer appears on the Summer Solstice. Public access to the site was cut off by the National Park Service in 1989 when erosion caused by foot traffic was found to be the cause of the shifting. In 1990, the slabs were stabilized and placed under observation though the titled rock was not re-aligned.

The ruins at Chaco Canyon continue to attract and inspire visitors the world over. Much of these people’s culture and ways of life are lost to time or enshrined in the spiritual beliefs and oral histories of the modern day Native tribes of the American Southwest. The Sun Dagger remains an enigmatic piece of a centuries old puzzle that points to the astronomical and mathematical sophistication of the Chacoan People.