Mysterious West is a free publication and podcast. However, if you enjoyed this episode and want to support my work, consider donating to my caffeine addiction. Thank you for reading.

-J.D. Wicks

A familiar shape emerges from a bank of heavy fog. The ghostly shadow of a man coalesces before your very eyes. You instantly recognize the long, dark coat and grizzled features of a certain wanted man. Your posse has been trailing this fugitive for too many days and countless more miles, all for the crime of robbing a bank. Everyone present knows this man can’t be trusted, yet the outlaw feigns surrender anyway. When the shooting starts, your trigger finger is ready. Suddenly, the gun bucks and a trio of barrels spout flame as though they were a single weapon. With the bandit disarmed, you can now see the grisly ruin left in the wake of hot lead. Three bullets have perforated the man, paralyzing him from the waist down. While outlaw Oliver Yantis would live just one more agonizing day, exactly whose bullet took the man’s life might just always remain…a mystery.

On November 29, 1892, Oliver Yantis lay upon the ground at his sister’s farm, bleeding to death from a series of heinous gunshot wounds. While the man would live a little while longer, tended to by the lawmen who shot him, Oliver Yantis would ultimately die later that day.

At first glance, there’s no mystery here to solve. There’s no question of the dead man’s identity and motive for the killing was more than obvious. The men present at the scene are well-documented as well, eliminating a need for suspects.

Where then, is the mystery?

The open-ended question arises when we examine the corpse of the deceased Oliver Yantis, keeping in mind that all three bullets were delivered by different individuals at the exact same time. Under normal circumstances, there would be few questions over which shot had ended the outlaw’s life. However, in this particular circumstance, there was a hefty sum of money at stake. You see, Oliver Yantis was a member of a criminal enterprise known as the Dalton-Doolin Gang. There was a reward on his head, and only the man who did the killing got paid.

The Dalton-Doolin Gang, also known as the Wild Bunch, the Oklahombres, or the Oklahoma Longriders on account of the long duster jackets they wore, terrorized whole swaths of the Midwest and Great Plains between the years of 1892 and 1895. Their three year campaign of crime twined through the states of Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas, and the Oklahoma Territory. Typically, the gang preyed upon wealthy institutions like banks, trains and high-end mercantile. This penchant for “sticking it to the man” fostered an air of Robinhood-like status among those that sympathized with their cause, a tacked on legacy that follows more than one famous gang of killers and thieves. Throughout their tenure eleven men would find a place among the Dalton-Doolin ranks. All eleven would eventually meet their demise down range from a lawman’s loaded gun. One of the earliest members was the Kentucky born cotton farmer in question, Oliver Yantis. Coincidentally, after a short and rather unsuccessful criminal career, he would also be the earliest to die.

The Dalton-Doolin Gang had their beginnings within another famous outlaw band, the storied Dalton Gang. This group of robbers and ruffians was led by Bob Dalton and was mostly composed of his brothers and close kin. However, three other men also accompanied the Dalton clan, their names being Bill Doolin, George Newcomb, and Charley Pierce. All three of the men would be key players in the eventual escapades of the Oklahombres. Bob Dalton and his posse were responsible for carrying out dozens of crimes that included horse theft, bootlegging, and train holdups. On July 14, 1892, the Dalton Gang botched an attempt at a bank robbery in Adair, Oklahoma Territory. In the ensuing chaos, two guards and two doctors sitting on the porch of a nearby Drug Store were struck by Dalton bullets. Three of the men were wounded but eventually recovered. The fourth, a man recorded as Dr. Goff, perished from his injuries the very next day. In the aftermath, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad offered a $40,000 reward to anyone able to capture and convict the gang in its entirety. In addition, a $5,000 bounty was placed on each individual member. This turn of events would lead to the quick dissolution of Bob Dalton’s band of brothers.

While the true reason for the break up is lost to history, it seems to have been spurred by brewing internal conflict. In one version of the story, Doolin, Pierce, and Newcomb complained that the Dalton boys weren’t splitting the loot fairly. In another, Bob bluntly told the three outsiders that their services were no longer needed. Regardless of the grounds, it was in their best interest to leave. Shortly after the split, four out of five remaining Daltons would die in the famed Coffeyville Raid in Coffeyville, Kansas on October 5, 1892.

Now free from the yoke of Bob Dalton, Doolin and his partners carried out a number of crimes in the Oklahoma territory with the aid of Henry Starr. Henry, a mixed-blood Cherokee and nephew to the infamous “Outlaw Queen” Belle Starr, once claimed to have carried out more robberies than any other man in America. Eventually, Doolin and company returned to share their condolences to the Dalton matriarch in Kingfisher, Oklahoma. Coincidentally, the remaining Dalton brothers Lit and William were also there when the three arrived. While conversing, Doolin proposed that they form a new gang to avenge the deaths of their dearly departed. Lit was appalled at the suggestion and rejected the offer outright. William, on the other hand, was all in. It was here that the Dalton-Doolin Gang was officially formed.

Just a week after the failed Coffeyville shakedown, Bill Doolin and William Dalton began planning their first robbery as the newborn Oklahombres. Throwing in his lot with the desperados was young Oliver Yantis. While his birth date eludes the history books, it is known, at least according to his obituary, that Kentucky was his homeland. Before taking up a gun, Oliver tended cotton in what is now Orland, Oklahoma. Little is known about Oliver’s life before joining the gang, making his prior history as unremarkable as his brief life of crime. It is said that he first met Bill Doolin through George Newcomb who was courting Oliver’s sister at the time. On October 6, 1892, Yantis aided Newcomb in holding up a train near the town of Caney, Kansas. While technically successful, the pair only managed to escape with $100 cash money. While not necessarily a sum to scoff ate, this take would pale in comparison to the gang’s later operations. Then, on November 1st of the same year, less than a month after the Caney robbery, Yantis would participate in the highlight of his short-lived career.

As the story goes, in late October of 1892, three strangers sought rooms at a boarding house in Garden City, Kansas. Coincidentally, Garden City was also home to Newton Earp, the less famous half-brother of legendary Wyatt. Many assumed the riders to be from Oklahoma or Texas, though their stories never quite seemed to make sense. While there, the men would take extended leaves of absence, traveling by horse or train, and returning a few days later. The men were consistently tight lipped about their doings, fostering suspicion among the other guests. Then, on October 28, the men checked out of their rooms and rode east out of town just as quiet as they’d rolled in.

On November 1st, the strangers appeared again in the small town of Speareville, Kansas, located just 17 miles from the infamous Dodge City. Shortly after their arrival, the trio dismounted and two of them sauntered into the Ford County Bank. According to the report, one of the men engaged a cashier, documented as J. I. Baird, in conversation about procuring a personal loan. In hindsight, this inquiry seems to have been a calculated distraction, buying the others time to scout their surroundings. Suddenly, one of the strangers drew a revolver from his belt, waving it in Baird’s direction while demanding he throw up his hands and surrender. Acting quickly, the cashier dropped behind the counter and snatched a pistol hidden below. As quick as Baird may have been, the bandits were faster. When the cashier leapt to his feet, preparing the gun to fire, he was greeted by the sudden strike of a pistol butt, rapidly disarming him of both firearm and accompanying courage. At the robber’s demand, Baird forked over $1,697 in First National Bank of Dodge City and U.S. Treasury Notes. Despite the sizable sum, the men once again failed to strike the mother lode. Sitting hidden beside the bank notes was a modest cache of gold and silver that Baird had neglected to mention.

Loaded with cash, the two bank robbers fled the scene using the cashier as a human shield and joined their third companion who was waiting with horses nearby. While racing out of town, the three outlaws encountered a group of men returning home from a hunting expedition. Upon realizing what had happened, the hunters quickly turned around and gave chase. The hunters and bandits exchanged fire but the outlaws managed to escape. Later, a mounted posse overtook the fleeing bandits and another running gun battle ensued. Yet again the Oklahombres evaded capture. In both exchanges, not a single individual was maimed or killed. In the dead of night, the three robbers were able to cross the Rock Island railroad tracks near Bucklin and were later spotted passing by Ashland heading straight for Oklahoma Territory. Crossing the border in the dim light of breaking dawn, the contingent of criminals believed themselves safe within the bounds of No Man’s Land.

Throughout this entire ordeal, the outlaw’s faces were in full view of cashier J. I . Baird. When asked to provide a statement, Baird was able to supply law enforcement with detailed descriptions of each individual. According to the reward notice, “One of the robbers was a medium sized man with a two weeks' growth of sandy beard and wore dark clothes and a white hat. Another was a young man, small in size, with dark complexion, and small, dark mustache and dark eyes. The third was of medium size, rather young, with a dark mustache, dark clothes and a light hat.” Baird was even able to identify the breeds of horses and the color of their manes.

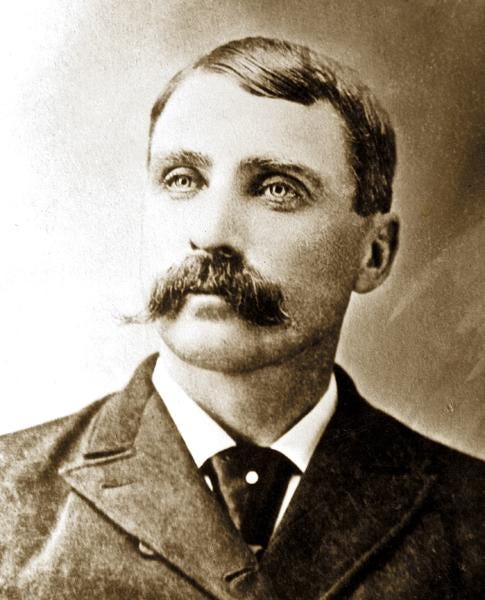

When word of the robbery reached Dodge City, Ford County sheriff Chalkley McArtor Beeson vowed that the perpetrators would be brought to justice. Chalk Beeson was born on April 24, 1848 and rapidly became a prolific member of Western society. Born in Salem, Ohio, Chalk was the seventh son of Samuel and Martha Beeson. Shortly after his birth, the entire family moved to Marshalltown, Iowa. At the age of 18, Chalk moved from Iowa to Texas where he became employed as a cowboy. While there, he had the opportunity to work with notable Charles Goodnight who later claimed Beeson “was the best cowboy on the trail”. He went on to say that Chalk “could stampede or quiet a herd quicker than any rustler I ever met." After working the range for six years, Chalk traveled to Colorado where he was a guide to Buffalo hunters. Among his clients were a handful of high profile characters of the age, including Union General Philip Henry Sheridan, George Armstrong Custer, and the Grand Duke of Russia, Alexei Alexandrovich. While in Colorado, he became an active member of the Pueblo community, volunteering for the local fire department and playing on the Pueblo baseball team. For a time, Chalk drove a stagecoach to and from Denver, but eventually decided to move back east, settling on Dodge City as his final destination.

While living in Dodge City, Chalk took a brief interlude back to Marshalltown, Iowa, where he married a woman named Ida Gause on July 17, 1876. Groom and blushing bride had planned on moving to Kansas City, Missouri but Beeson was called back to Dodge in order to procure money owed to him by the owner of the Billiard Hall Saloon, A.J. Peacock. Upon their arrival, Peacock informed Beeson that he could not pay, instead offering up the deed to the saloon. Chalk accepted. Changing the name to Saratoga Saloon, Chalk opted to provide the frontier town with an alternative form of entertainment when compared to the average drinking establishment. Instead of prostitution, Chalk provided guests with a full orchestra, injecting a much needed dose of culture into the rough and tumble Western town. Building upon his success, Beeson also purchased the Long Branch Saloon and established the COD Cattle Ranch with his partner William H. Harris. Never shying from his love of music, Chalk founded the Dodge City Cowboy Band in 1884. Members of the musical ensemble were clad in ostentatious cowboy regalia, including comically oversized white Stetson hats, flannel shirts, and ornamental spurs. On March 4, 1889, the Cowboy Band played in President Benjamin Harrison’s inaugural parade. Finally, after a life of travel and successful business ventures, Chalk Beeson was elected sheriff of Dodge City in November of 1884 at the age of 43. This new appointment would set him on a path leading straight to the Oklahombres and runaway Oliver Yanits.

Upon catching wind of the Speareville robbery, Beeson had Wanted notices printed on penny postcards offering a reward of $450 alongside descriptions of the men and horses. The cards were mailed out to every nearby community with a post office that very same day. Chalk’s plan was to pepper the frontier with these postcards, putting any cowtown or farming community on notice. He figured the perpetrators would have to show up somewhere eventually, and when they did, he wanted to hear about it. Two weeks went by before Beeson received word of the trio’s movements, but his information campaign had paid off. On November 15, a letter came in that claimed three men matching the postcard’s description had arrived in Stillwater, Oklahoma Territory. Sheriff Beeson immediately sent John Curran of Garden City, one of the men who had been at the boarding house when the strangers arrived, to acquire positive identification.

Upon arriving in Stillwater, Curran was led by Hamilton B. Hueston to a farmstead near Orlando, Oklahoma owned by one Hugh McGinn. According to the local testimony, a man fitting the postcard description was hiding out there. Upon further investigation, Curran and his accomplice discovered that McGinn had a brother-in-law named Oilver Yantis who was a perfect match. On December 24, 1892, Curran swore in an official affidavit that he met and recognized Oliver Yantis as one of the strangers from the Garden City boarding house. In a similar affidavit, Hamilton Hueston claimed that Yantis was obviously uneasy with their introduction, keeping his gun hand on a revolver at all times. After the meeting, the pair rushed back to Stillwater and immediately wrote a letter to Sheriff Beeson to report their findings.

Emboldened by Curran’s letter, Chalk Beeson departed for Stillwater and arrived on November 28. However, Beeson had to leap one more hurdle before making his move. While Chalk was an appointed peace keeping official in the state of Kansas, he had no jurisdiction in the Oklahoma Territory. Before moving on Oliver Yantis, Beeson had to travel to the territorial capital of Guthrie to secure proper authority and a warrant for Oliver’s arrest. There was no contest to Beeson’s claim and he was promptly made an officer of the Territory of Oklahoma for the purpose of pursuing and detaining Yantis. To carry out the now lawful operation, Beeson recruited city marshal Thomas J. Hueston, Hamilton’s brother, and U.S. deputy Marshal George Cox to accompany them to the McGinn farmstead in Orlando.

While Hueston’s aforementioned affidavit goes on to give a brief description of the meeting, the Dodge City Globe-Republican newspaper published a detailed account of the conflict in their December 2, 1892 edition. Somewhere along the ride, Beeson discovered Doolin and Newcomb had also been seen in the area though they had long since fled. It was assumed that they were headed into the Creek Nation seeking to cover their trail. Chalk Beeson recognized the urgency in pursuing the two runaways that had flown the coop, but his sights were already set on taking Oliver Yantis. On November 29, 1892, Beeson, Cox, and the Hueston brothers arrived at McGinn’s farm at roughly 6:30 am. As to not arouse suspicion, they dismounted out of sight and hid their horses. Slowly, the posse moved into position between the house and the corral where a number of horses were kept. The idea was to cut off any quick means of escape. They did not announce their presence, instead opting to wait and hope that Oliver ventured out of his own accord. Beeson, for all his grit, wanted to take Yantis alive and didn’t want to risk the outlaw barricading himself inside the home. Eventually, about half an hour after their arrival, Yantis made his appearance.

In the dim twilight of that late autumn morning, a figure began to move through the drifting fog. It wasn’t until the man was within fifty feet that a positive identification could be made. Beeson quickly announced their presence, demanding Yantis surrender. Instead of complying with the command, Yantis jerked his revolver from its holster and fired. The bullet missed Beeson and spurred Hamilton Hueston to action. Swinging his shotgun to bear, Hamilton pulled the trigger but nothing happened. Perhaps it was the cold, damp atmosphere, or even dumb luck but regardless the cuase his scattergun had misfired. Yantis sent another shot down range and then was met with a wall of flying lead. Beeson, Tom Hueston, and Marshal Cox all fired at Yantis in one volcanic instant, leveling the cotton farmer flat upon the ground. Yantis, however, had not yet given up the ghost. Oliver continued to fire, emptying every chamber in the six-gun. One of the stray bullets grazed George Cox, sending him into a fury. Beeson stopped the man from charging, pointing out that Yantis was badly injured. Still, Oliver reloaded his gun and continued to fire wildly, unable to see where the lawmen were hiding.

Drawn outside by all the shooting, Oliver’s sister eventually put an end to the standoff by convincing the wounded outlaw to surrender his gun. When Beeson and his men finally laid eyes upon Yantis, they knew there was little to be done for the man. One bullet bore through his right side above the hip at a downward angle, severing the spine. A second shot had drilled Yantis in his leather pocketbook that contained a stack of bills lifted from the Spearville Bank. The billfold and bills served as poor protection as the bullet perforated the full way through. At this point, their only option was to get Yantis to a nearby doctor. By the time the party had arrived at the physician, there was nothing to be done for the man. Oliver Yantis died in bed at 1:00 in the afternoon, a curse for the officers still lingering on his lips. Despite his brief career as a robber and semi-notorious bad man, Yantis remained belligerent to the bitter end. After all was said and done, he made no admission of guilt or confession of his crimes.

Despite lacking a confession, Beeson was sure that Oliver Yantis had been guilty. His clothing and overcoat were just as witnesses described, bank certificates on his person were identified as having been taken from the Spearville bank, and even his style of boots and hat were identified from the robbery. In the aftermath of it all, Beeson commissioned a tasteful photograph of a restful Oliver as confirmation of the outlaw’s death. The $55 found in his bullet-riddled billfold were turned over to Chief Deputy U.S. Marshal Chris Madsen on November 20, 1892 for which Beeson received a receipt. The corpse of Olvier Yantis was claimed by his sister who had him buried in the Roselawn Cemetery in Logan County Oklahoma, punctuating the end of the outlaw’s life of crime.

But what of the reward money mentioned before? Who’s bullet had sent young Oliver to meet his maker? As it turns out, a number of people were implicated in the killing. Interestingly, some of them weren’t even present at the afformentioned gunfight. These mixups were likely due to technological limitations and the relatively slow speed at which information traveled, causing a prolonged game of telephone with the truth. Worth noting as well is the tendency for news outlets of the time to report events through a lens of sensationalism, making the facts even harder to discern. For example, the very same Dodge City article that details the shootout at McGinn’s farm also goes on to describe Oliver’s sister as both beautiful and practiced in the art of a fast draw. Now, both of these particular details could in fact be true, and who I am to question whether or not Mrs. McGinn was an alluring specimen? Still, the addition of frivolous yet titillating details begs for deeper scrutiny.

Among the accused killers was none other than Marshal Chris Madsen, the official that received Oliver’s remaining loot. Later, it would be discovered that Madsen was nowhere near the vicinity of the shootout when it happened, effectively kicking him off the lineup. Another source credits Tom Hueston. Though his involvement in the ordeal is without doubt, it does make one wonder why Cox and Beeson were left out of the picture. Still, at least Tom was actually present at the gunfight, which is more than Madsen can say. In truth, any one of the three bullets could have done the job and while medical science was making great strides at the turn of the century, forensic analysis was not yet up to snuff.

That leaves a single, admittedly shakey, piece of evidence.

Who claimed the money?

If only the outlaw’s slayer could claim the reward, who then took the pot?

This is where Chalk Beeson once again enters the story. Documents found within the archives of the Kansas State Historical Society provide a record of Beeson’s attempt at securing the reward for Oliver Yantis. Sheriff Beeson presented sworn affidavits and the photographic evidence of Yantis’ death to Kansas State Governor Lymen U. Humphrey, who rejected Beeson’s claim. The reasoning behind this eludes telling, but the case was once again brought before Humphrey’s successor, Lorenzo D. Lewelling, when he took office only a few weeks later. The new governor disagreed with his predecessor’s assessment and signed off on the payment of $450. In most tellings, Beeson had made a verbal agreement to split the reward with his compatriots, the Sheriff taking $300 and his partners taking the remaining $150 between them. Whether or not this agreement was fulfilled, or even agreed upon, seems left to conjecture. Based solely on records and articles praising Chalk Beeson’s character, it seems likely he wasn’t one to be bested by greed.

It seems, at least in a court of law, Sheriff Chalkley Beeson was recognized for putting an end to the criminal career of Oliver Yantis.

After Speareville, Bill Doolin and the Oklahombres carried out a successful rash of robberies and train hold ups throughout the region. In March, 1893 Doolin married Edith Ellsworth in the town of Ingalls, Oklahoma. After robbing a train in Cimarron, Kansas, Doolin was shot in the foot by law enforcement, prompting the gang to retreat back to Ingalls. On September 1, 1893, a force of 14 deputy U.S. Marshals confronted Doolin and his gang, including both George Newcomb and Charley Pierce. The ensuing gunfight is now remembered as the Battle of Ingalls. During the conflict, two bystanders were slain, and one wounded, three gang members were killed, as well as three Marshals, including Tom Hueston. The Battle of Ingalls elevated the gang’s notoriety and the fleeing members were pursued relentlessly by federal agents and bounty hunters alike. Marshal Chris Madsen led one group, known as the “Three Guardsmen”, which also included Bill Tilghman and Heck Thomas. Fate finally caught up with Newcomb and Pierce on May 1, 1895, when a pair of bounty hunters called “The Dunn Brothers” found them at the ranch of Newcomb’s lover. Interestingly, the Dunn’s were the older siblings of the aforementioned girlfriend, Rose. As for Bill Doolin, he was captured in a spa at Eureka Springs, Arkansas in early 1896, presumably alleviating the rheumatism in his injured leg. He escaped jail on July 5 and fled to Lawson, Oklahoma with his wife. On August 24, he was confronted by one of the Three Guardsmen, Marshal Heck Thomas, and was killed by a shotgun blast. At the close of 1898, every remaining member of the Dalton-Doolin gang had joined Oliver Yanits in eternity, mostly at the hands of Madsen, Tilghman, and Heck.

As for Sheriff Chalkley Beeson, he served two terms as Sheriff and was lauded as a hero by his community. Afterward, he spent much of his time focused on his cattle ranch while continuing to be an active member of the community. He also served four terms in the Kansas State legislature from 1903 to 1908. His story, however, would come to a far less dignified end on the morning of Tuesday, August 6, 1912. After completing his morning routine, Beeson mounted a particularly skittish horse. After a brief ride, he went to dismount and something set the animal off. The horse bucked, and sent the aged Beeson crashing into the dirt. He survived for another two days though he suffered from internal hemorrhaging. Chalk Beeson eventually passed away on August 8, 1912. He was buried in the Maple Grove Cemetery in Dodge City, Kansas. Despite his less-than-dramatic demise, Beeson’s family continued to keep his spirit alive. Today, a large collection of Chalk Beeson’s effects, including photos, artifacts, and documents, are held in Dodge City’s Boot Hill Museum. And if you happen to find yourself perusing the rolling plains of Kansas in the midst of summer, you can still catch the Dodge City Cowboy Band performing for locals and tourists alike.

So, in the end, was it truly Chalk Beeson who put outlaw Oliver Yantis in his grave? Or, as Lymen Humphrey claimed, did the Dodge City Sheriff lack sufficient enough evidence to procure the posted bounty? Perhaps it was one of Beeson’s three compatriots who pulled the deadly trigger. Unfortunately, without the capabilities of modern investigative technology the owner of the bullet that killed Oliver Yantis will forever remain a mystery.

Selected References:

http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/daltons.htm

https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~beeson/genealogy/chalkley.html

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/we-billdoolin/

https://truewestmagazine.com/article/a-short-and-not-so-sweet-career/

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/oliver-yantis/

https://truewestmagazine.com/article/chalkley/

Hunt, D. & Snell, J. “Who Killed Oliver Yantis?”. Ture West Magazine, February, 1966.

Samuelson, Nancy B. "Dalton Gang". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Oklahoma Historical Society.

"Starr, Henry | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture". www.okhistory.org.

Share this post